If you thought single malts weren’t widely sold outside Scotland before the 1960s, then think again. The historical record shows that this style of whisky was popular throughout the UK more than a century earlier, as Iain Russell reports.

Early reference: A 19th-century Royal Brackla ad exploits the whisky’s regal

You will have heard the story told many times. How single malt Scotch whisky was virtually unknown and unobtainable outside Scotland before the 1960s. It was told for decades by people in whisky sales and marketing, and repeated faithfully by credulous journalists. And it’s a load of old tosh.

Single malt Scotch whisky, made in a pot still and preferably in the Highlands, was already very popular in Scotland by the 1820s. There had been a general condemnation of much of the whisky produced by the large Lowland distilleries. Leading distillers like the Haig’s and Steins adopted rapid distillation techniques to evade steep excise duties levied on still capacity, and their processes were said to produce a harsh, unpalatable spirit. While it might be adequate for rectifying to make gin, large quantities of this cheap product were supplied to Scottish shops and inns.

Consumers, especially the wealthier ones, preferred to pay a little more for the ‘real thing’ – whisky made from malted barley in small stills in the Highlands. It was this type of whisky, often distilled in the glens around Strathspey and known generically as ‘Glenlivet’, which was famously sought out by Sir Walter Scott for King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822.

There is no doubt that royal patronage helped establish the respectability and reputation of Scotch malt whisky in England. Captain William Fraser, for example, obtained a Royal Warrant for his single malt whisky from King William IV, and Royal Brackla was advertised heavily in English newspapers. Both Captain Barclay and then John Begg were able to solicit Royal Warrants for Glenury Royal and Royal Lochnagar respectively.

Royal approval: The finest ‘Glenlivet’ was sought for George IV’s 1822 Edinburgh visit.

Royalty’s interest in single malt Scotch whiskies was not confined to the products of what were known as the ‘north country distillers’. As early as 1841, a member of the Royal Household wrote to Daniel Campbell of Islay requesting supplies of ‘your best Islay Mountain Dew’ for Queen Victoria’s cellars.

Yet it seems that the Royal Family was merely following drinking fashion. Single malts from Scotland were sold in England throughout the 19th century. Although it remained a ‘niche’ market and sales were only a fraction of those achieved by blends after the 1850s, the ‘real mountain dew’ reached all corners of the country, especially as the railway network developed.

Blended Scotch whiskies – made by mixing single malt Scotch with cheaper grain spirit made in continuous stills – became increasingly popular during the second half of the 19th century. Yet, despite the efforts of reputable brand owners such as Walker, Dewar and Buchanan, cheap blended whisky had a bad reputation, and was often harsh and reputedly adulterated in public houses and other outlets. Many of the most respected wine and spirits merchants in English towns and cities continued to boast a single malt or two in their price lists, with distilleries such as Glen Grant, Talisker and Smith’s Glenlivet featuring prominently.

An agency representing Glenmorangie went so far in 1872 as to set up a London depot stocked with 20,000 gallons of its single malt, to supply whisky to a network of outlets established in cities and towns such as Oxford, Ipswich and Leicester. Mackie & Co-established a network of outlets stocking Lagavulin in the 1880s, when the brand was advertised as a seven- and a 12-year-old with ‘a worldwide fame’. Long John’s Dew of Ben Nevis was another popular ‘brand’.

Drinks companies from other parts of the UK were also keen to exploit the continuing, if ‘niche’, popularity of Scottish single malts.

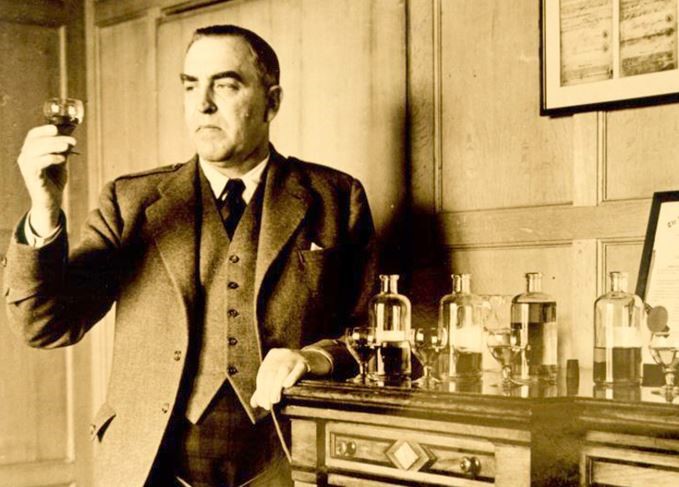

Malt man: Bill Smith Grant continued promoting The Glenlivet despite the success of blends

W&A Gilbey, for example, warehoused many thousands of gallons of whisky at the Roundhouse in London. The company promoted its Strathmill and Glen Spey single malt brands heavily, and exported them around the world. The Irish firm J&J McConnell invested in an expensive advertising campaign for its OO brand, a single malt from Stromness in Orkney.

And then there were the specialist bars. John Stewart, an Edinburgh man, established ‘The Clachan’ chain of specialist bars in Scotland and London, where one could sample whiskies such as Talisker, Caol Ila or Glen Grant at between five and 16 years old. The Edinburgh bar, located on The Strand in London, was also popular. Other cities boasting malt whisky specialist bars included Leeds, where the Viaduct Bar carried a vast range of single malts aged from five years and up to 10 years old.

Meanwhile, single malts retained a toehold in markets in English-speaking countries around the world. In 1840, a wine and spirits merchant in Whitehall Street, near Battery Park in Manhattan, advertised: ‘Scotch whiskeys [sic] from the celebrated distilleries of Drummin, Glenlivet and Ardbeg’. Islay whisky from Port Ellen and Ardbeg seems to have had a steady market in the US, and by the 1890s it was possible to buy a case of Ardbeg in Manhattan for only $11. Islay single malt whiskies were also popular in Australia and New Zealand.

The embryonic malt whisky brands entered challenging times in the 1880s. There was a general drift in the public’s taste away from stouts, peaty whiskies and other more strongly flavored and ‘challenging’ drinks; light, blended Scotches mixed with soda soared in popularity. Then, in 1898, the consequences of the infamous ‘Pattison Crash ’left distillers with thousands of casks unsold to blenders and a ‘whisky lake’ that was not drained for many years.

Big in America: The Glenlivet was in huge demand in the US during the postwar period

Led by George Smith Grant of The Glenlivet, the ‘north country distillers’ tried to find a legal definition for Scotch whisky which would differentiate more clearly between single malt and blended Scotch. In 1909, however, they had to admit defeat when a Royal Commission ruled that “Whiskey” [sic] is a spirit obtained by distillation from a wash saccharified by the diastase of malt, that “Scotch Whiskey” is whiskey, as above defined distilled in Scotland.’

The 1909 ruling was a triumph for the whisky blending houses, and blended Scotch brands led by Johnnie Walker, Dewar’s and the like became famous around the world. Only Bill Smith Grant at The Glenlivet appears to have been willing to continue to invest in the promotion of a single malt at home and abroad.

After Prohibition ended in December 1933, Smith Grant travelled to the US on several occasions to establish agencies to distribute The Glenlivet in the country, and he went back after the Second World War to renew his efforts. By 1963, although hindered by shortages of stock, the firm was selling 3,000 cases per annum in the US, and had laid the foundations for a highly successful business there. It remains the top-selling single malt in the US today.

In the late 1950s, brands such as Glen Grant and Glenmorangie were relaunched, and it was discovered that there was a widespread appetite for single malts among connoisseurs – Glen Grant 5 Years Old, indeed, was for a time the top-selling Scotch brand in Italy. In 1963, Glenfiddich relaunched alongside The Glenlivet in the US, and was an immediate success. Single malts have gone from strength to strength since then, and it seems inconceivable today that they will ever fall out of fashion again.